Hitting a double

March/April 2023 California Bountiful magazine

Nurseryman has had

two rewarding careers

Story by Linda DuBois

Photos by Tomas Ovalle

It’s that time of year baseball fans have anticipated through the cold winter months, when they can finally file into a stadium, grab their hot dogs and peanuts and enjoy America’s national pastime.

Jon Reelhorn is one of those fans—and he can watch a game through a lens most can’t. He remembers being the one all eyes were on after the umpire exclaimed, “Play ball!”

Now the owner of Belmont Nursery in Fresno, Reelhorn was a professional baseball pitcher before he grew and sold plants.

When he occasionally looks back on his time in baseball, he realizes it helped shape the person and businessman he is today and gave him some of the best memories of his life.

Following a dream

Raised in Stockton, Reelhorn grew up playing baseball. He recalls the moment that changed the trajectory of his future. As a sophomore on his high school team, he was practicing pitching fastballs when the catcher suddenly stood up and said, “Hey, that one moved! It tailed inside.”

“I asked him, ‘Is that good?’ and he said, ‘I think so,’” Reelhorn recalls, chuckling.

It turned out to be very good.

“The beauty is it was just God given. I just threw the ball and it wouldn’t go straight. But it opened up all these opportunities I wouldn’t have had otherwise,” Reelhorn says.

He was recruited by several colleges and drafted by his favorite team, the San Francisco Giants, but he chose to accept a scholarship to California State University, Fresno.

“I remember how difficult of a decision that was,” Reelhorn says. “But the best decision I ever made was to go to school instead of the low minor leagues.” Fresno State provided great coaching and facilities, an education and the fringe benefits of college life like “girls and fun and parties.”

He credits Fresno State’s longtime baseball coach Bob Bennett for turning the “young cocky prima-donna kid” into an adult.

For Reelhorn’s first scheduled big game as a freshman, his whole family came from out of town to see him pitch. But he was late for warmups—and Bennett sent him home. “It just made me understand that it doesn’t matter if you’re a good player or not—there are rules. So, it was a really good lesson for me. You’ve got to take responsibility for yourself.”

Off to the farm team

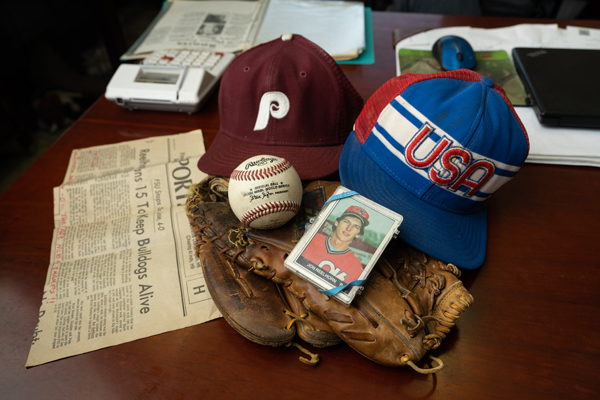

In 1980, his junior year, the Philadelphia Phillies drafted him, assigning him to the Double-A Reading Phillies.

The following spring, he was the last of about 25 pitchers to be invited to major league training camp, where he played alongside the likes of Mike Schmidt, Steve Carlton and Tug McGraw. “My locker was right next to Pete Rose’s!” he remembers.

The first exhibition game, Reelhorn pitched the middle innings. From the mound, he looked around at his heroes and thought, “‘What am I, Jon Reelhorn, doing here?’ It was just a thrill!”

Reelhorn played through the spring, watching pitchers get cut from the roster until there were 11 prospects left. “They were going to take 10,” he says.

The second to the last day of camp, the trainer tapped Reelhorn’s shoulder and said the manager wanted to see him. Reelhorn’s heart sank. “I knew that meant I was the last to get cut.”

So, he headed to the Phillies’ Triple-A Oklahoma City 89ers. His two seasons there, he lived out of a suitcase and made lifelong friends while financially scraping by playing the game he loved.

Hanging up the glove

Following an arm injury, his pitching suffered. He was released by the Phillies in 1983 but quickly picked up by the Giants, who assigned him to the Double-A Shreveport Captains in Louisiana. But he still wasn’t pitching well and again was released.

So, he worked harder than ever to get into top shape.

The Cincinnati Reds invited him to spring training, but at camp’s end, wanted to send him to A ball—a lower level than he’d ever played.

Realizing he would never be the pitcher he once was, Reelhorn politely declined and also passed up their offer to coach. “I was ready to return to the real world,” he says.

“When you’re first done, you’re bitter because things went wrong; your dream of making it (to the majors) didn’t come true. But now, I look back and say, ‘Gosh, what an opportunity! ... I get to visit the Hall of Fame and look at the plaques on the wall and say, ‘I played with five of those guys on the same team.’”

Building a new career

He returned to Fresno and finished his last semester, earning a degree in plant sciences. He worked in a hardware store’s nursery department before becoming a salesman for wholesale nursery El Modeno Gardens in Irvine. During his 15 years there, one of his favorite customers was Belmont Nursery, run by Jerry Palmer, son of Vic and Ruby Palmer, who founded the nursery in 1942.

When Palmer neared retirement age, Reelhorn expressed interest in buying the nursery. Palmer loved the idea but asked Reelhorn to first work for him for a year, without any promises.

“This was scary because I had bought a home and had a good job,” Reelhorn says. But he took the leap and became the general manager under Palmer’s mentorship in 2000, and in 2001, took over.

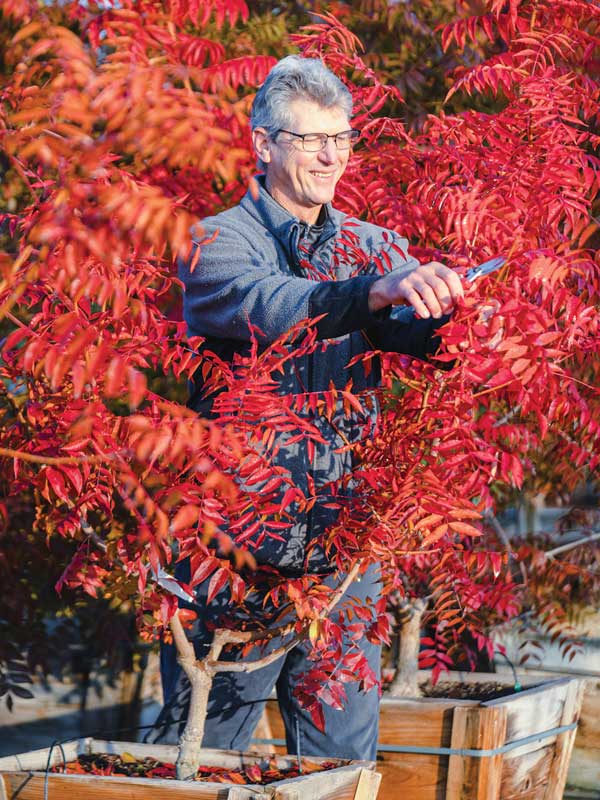

Reelhorn has expanded the site, the sales territory and the staff, from 13 employees to more than 60. He’s lost count of how many plant varieties the nursery carries, but they include bulbs, succulents, evergreens, perennials, shrubs, trees and vines.

He starts each day in the nursery, checking the plants and touching bases with employees.

“They all work with us because they want to, not because they have to for the money,” Reelhorn says. “I’m just so pleased with the staff.”

The game’s not over

Their proficiency allows Reelhorn the time to volunteer. Among other commitments, he’s the board chairman for the national nursery association AmericanHort and he’s been a Fresno County Farm Bureau board director since 2014.

The Farm Bureau’s CEO, Ryan Jacobsen, is one of Reelhorn’s few associates who knows about his baseball background. When Jacobsen learned this from a mutual acquaintance a few years ago, the sports fan did a quick internet search and Reelhorn’s 1982 baseball card popped up on eBay. So, he bought it.

“When I asked Jon to autograph it, he laughed,” Jacobsen says—but Reelhorn signed it, and Jacobsen keeps the card displayed in his office.

Reelhorn is less inclined to draw attention to his past but acknowledges it helped prepare him for his present.

“I learned as a pitcher that nothing happens until you throw the ball. Take risks. Be assertive. … And you have to control your emotions and always be a positive part of the team,” he says.

Grateful as he is for his time in baseball, Reelhorn finds his current career just as rewarding.

“Without the trees, without the flowers, without the beauty that we grow and distribute, we’re a concrete jungle, you know? We improve the quality of life for our community,” he says.

“I’ve been very blessed. The first third of my life, I got to chase my boyhood dream and it was great fun. The second third of my life, I got to be in the nursery industry and that’s been great fun. Pretty soon, I’ll have the last third of my life and there’s going to be volunteering or traveling or being involved in my church or whatever other opportunities life brings.”