Long cool ride

July/August 2022 California Bountiful magazine

Railroad transportation put farmers' goods on wheels

Story by Kevin Hecteman

B&W photos courtesy of California State Railroad Museum Library

The Gold Rush, as is well known, brought many a prospector to California in search of riches. Only it turned out they looked in the wrong place. It wasn't in the hills; it was in the fields.

After California joined the Union in 1850, miners gradually realized there were more reliable ways to make a living than panning for gold. Farming, for instance. Then, in 1878, the first practical ice-cooled refrigerator car was invented in Chicago. Aboard this invention, California agriculture would travel to prosperity.

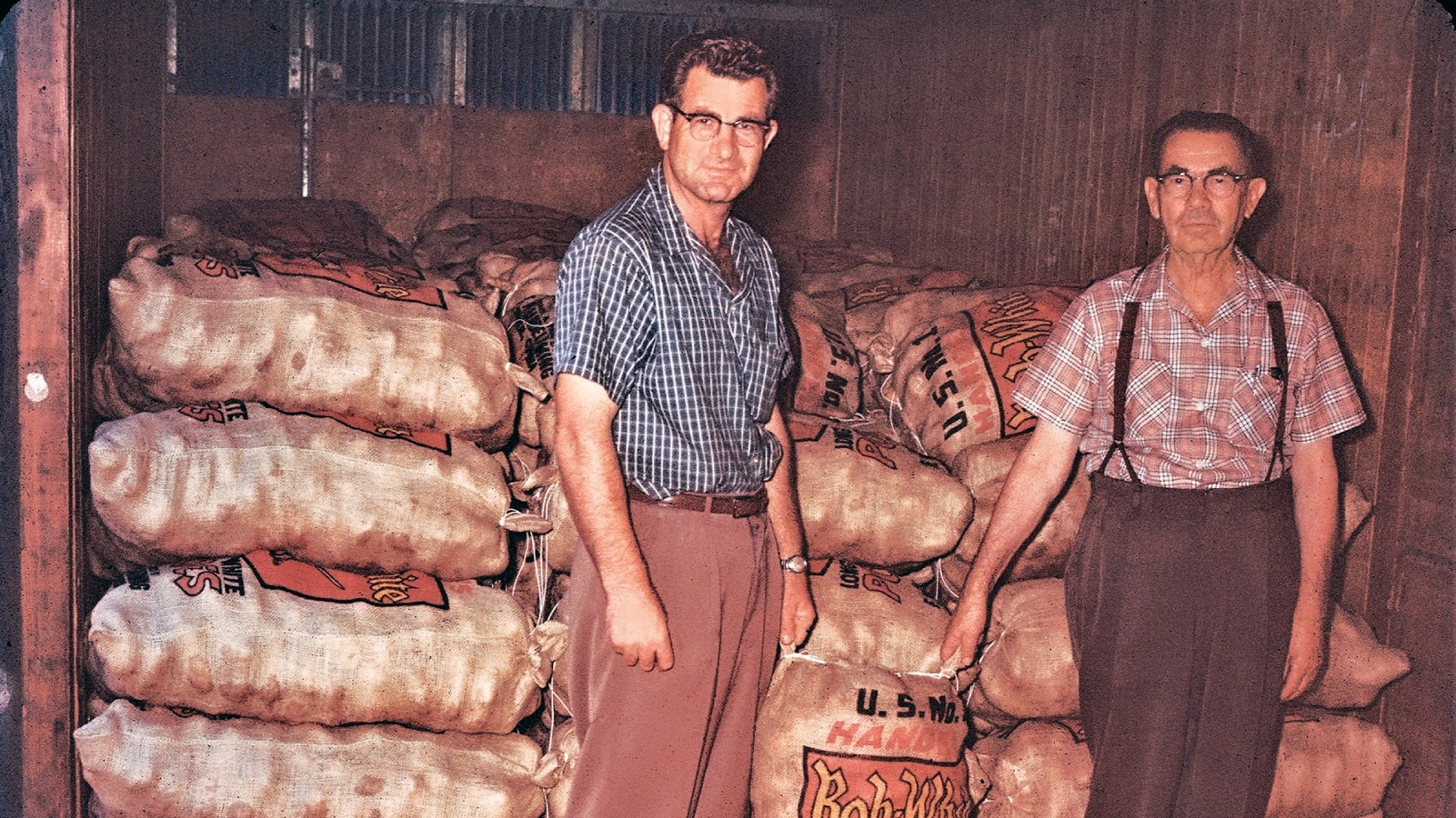

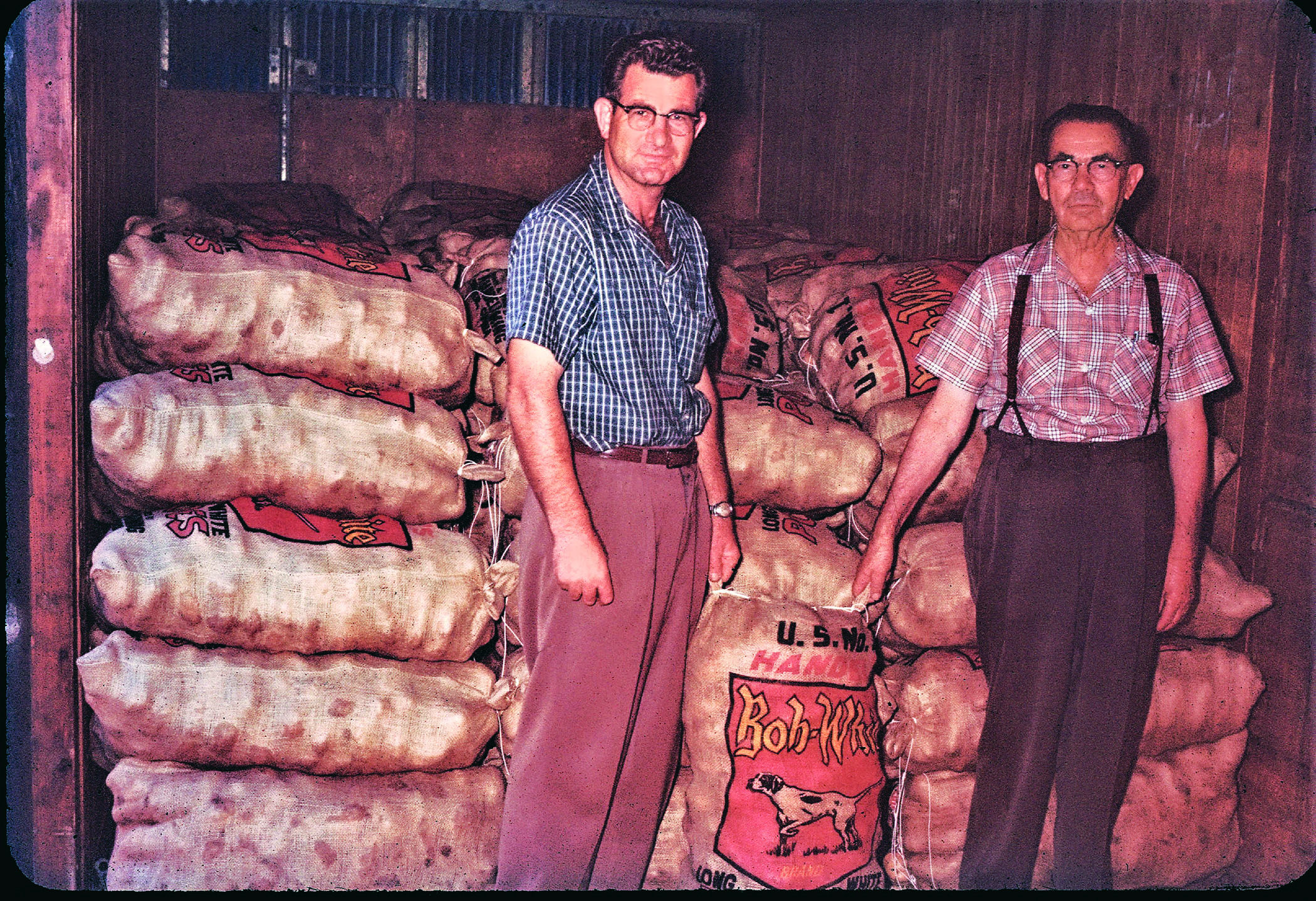

Stan Wilson is one farmer who knows the importance of steel rails to his crop. His family grew potatoes in the Shafter area for most of the 20th century and into the 21st; he got out of the business in 2016, after the last potato packinghouse in town closed.

But back in the day, Wilson and his neighbors counted on the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway to help turn California potatoes into Midwestern potato salad or New York baked potatoes.

"Without railroad transportation," he says, "there would not have been any potato industry to speak of here in Kern County."

Spuds on wheels

The Wilsons grew mainly White Rose potatoes, well suited to the soils around Shafter. Right after Christmas, farmers would prepare for planting.

"You would plant the potatoes in January, basically the months of January and February," Wilson says. From there, figure on about 120 days for potatoes to be ready for harvest, he added. "You would begin harvest late May and would go through early July"—emphasis on "early."

"My dad used to have a target date. He wanted to be done by the Fourth of July," Wilson says. "If we went past the Fourth two or three days, that was about it." That's in part because by mid-July, farmers on the west side of Fresno County started harvesting cantaloupes, creating tremendous demand for rail transportation.

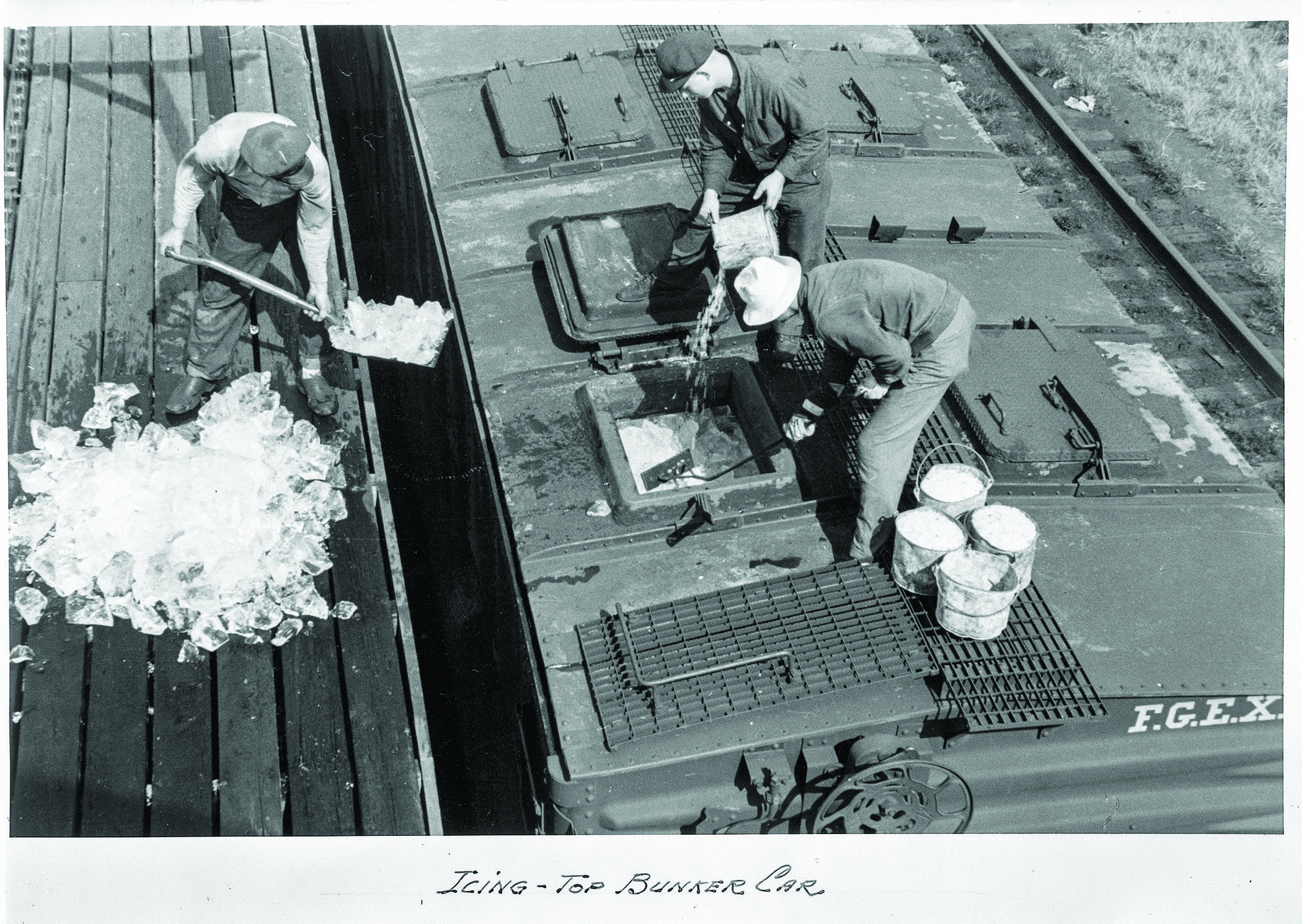

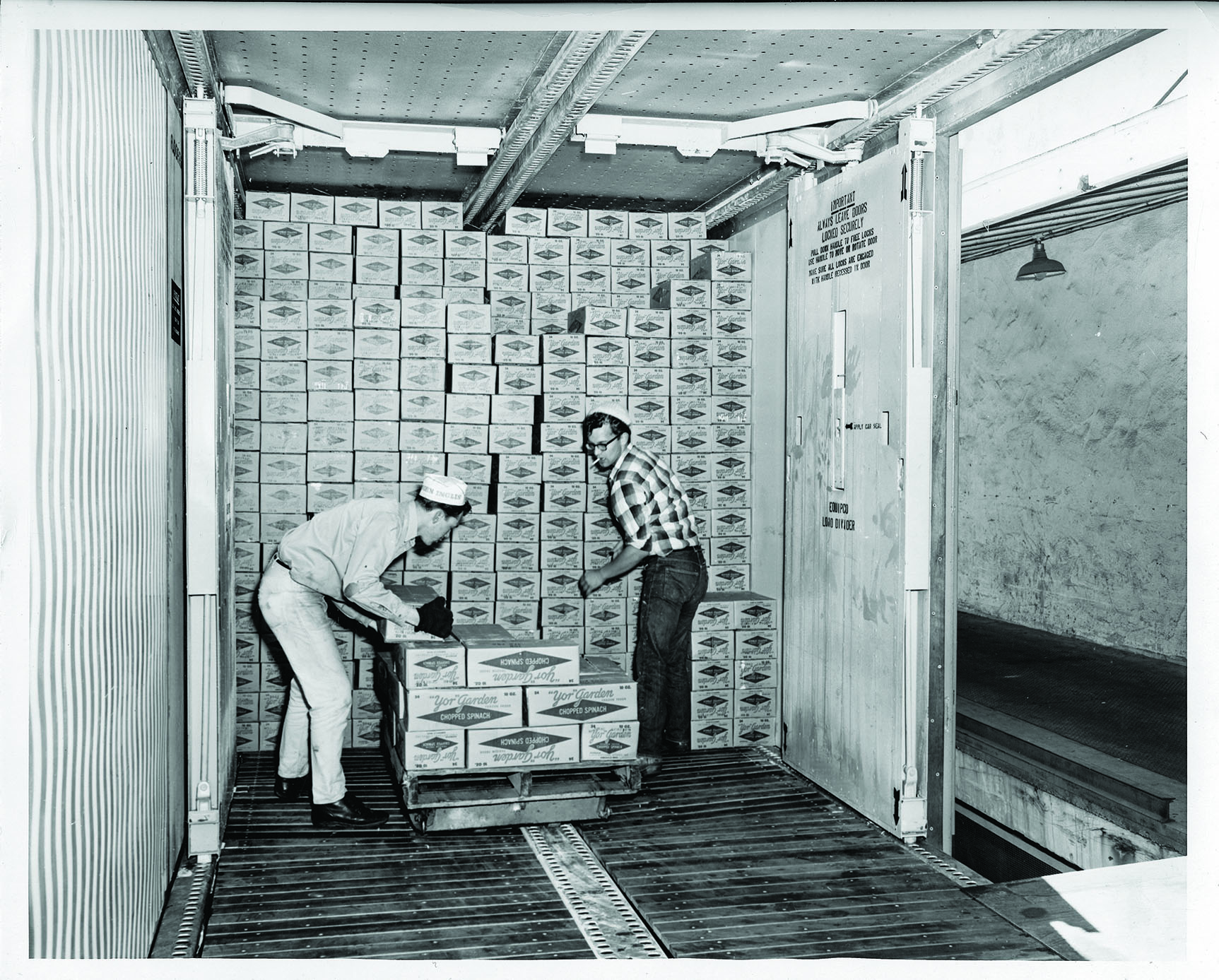

From the Wilson farm, potatoes went to a packing shed alongside the Santa Fe's mainline through town. The railroad would leave refrigerator cars on a spur track next to the shed for loading. Up until the 1950s, those cars would be cooled with ice, and farmers shipping crops to market in them would give detailed instructions as to how much ice was needed and how often it would need to be replenished, which the railroad would handle enroute. From the 1950s onward, mechanically cooled refrigerator cars became more common. "You just set the thermometer in the car and that was it," Wilson says.

From Shafter, Wilson's potatoes could land on dinner plates in … well, anywhere in the Lower 48.

"It could go virtually all over the country," Wilson says of the crop. "Many of them went into the Chicago gateway, and if they were going further east, they might go to New York, go up to Boston. They might go to the South."

(Rail)road to success

Wilson and his fellow farmers could do this in part because railroad magnates figured out early that one way to get rich was to help share California's bounty with the rest of the union.

Leland Stanford, the legendary railroad baron, recognized that the fortunes of the state's railroads and farmers would be tightly intertwined. Richard Orsi, author of the comprehensive Southern Pacific history "Sunset Limited: The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Development of the American West, 1850-1930," quotes a Stanford address to the State Agricultural Society in 1863 in which he proposed providing "the farming communities of the other states authentic information, in the shape of reliable statistics, as to the productions of our soil, and the noble field that is here offered for the industrious and energetic farmer."

(Stanford was multitasking before the term was invented. When he spoke those words, he had two jobs—president of the Central Pacific Railroad and governor of California.)

The Southern Pacific built the first rail connection from the Central Valley to Los Angeles via Tehachapi in 1876, seven years after the Central Pacific—an SP forerunner—met the Union Pacific in the famous Golden Spike ceremony at Promontory Summit in Utah. The only problem for valley farmers was that Southern Pacific had a monopoly—and acted like it.

"The rates were extremely high," Wilson says. "Even though they were used a lot for agriculture products, sometimes it was still cheaper for farmers to take their wagons and try to haul their products."

That, Wilson says, helped spur construction of a second railroad, the San Francisco & San Joaquin Valley, completed in 1898.

"It was known as the people's railroad, because basically it was built in competition to the Southern Pacific to lower the rates," Wilson says. "That created the competition in the state to get reasonable rates for agriculture products."

(Both railroads are still around, under different names. The SF&SJV was sold to Santa Fe in 1900 and is now part of BNSF Railway. The SP was merged into Union Pacific in 1996.)

The availability of water, the climate and soils, and the railroads' vigorous, decades-long promotion of California as the ideal place to live and raise crops all came together to help set farmers like Stan Wilson on the railway to success.

"They already had the climate and the soils," Wilson says. "Couple that together with irrigation and transportation to get the product across the country, and agriculture took off."

December 1906 saw the formation of one of the 20th century's most vital agricultural transportation enterprises: Pacific Fruit Express, which started operations the next month with a fleet of 6,600 refrigerator cars, according to Sacramento History Online. At its zenith, in the 1930s, the company—a joint venture of Southern Pacific and Union Pacific—had more than 40,000 refrigerator cars in service.

Semi-retired life

Even though the family doesn't grow potatoes anymore, the Wilsons still farm. The family now raises almonds, carrots and one field of cotton. While the railroads themselves are still in service, agricultural transportation is now almost entirely handled by trucks, a trend Wilson says began in the 1970s.

Though his son and son-in-law help, Wilson's still involved on the farm. Exactly how much is a matter of debate.

"My wife says I'm not retired," Wilson says. "I said I'm partly retired."

The author is a volunteer at the California State Railroad Museum.

Where to find it

Interested in learning more? The Shafter Historical Society has a museum in the former Santa Fe depot, of which Stan Wilson serves as curator. The depot houses, among other things, the Harlin P. Wilson Agricultural Museum (named for Stan's father). On display are vintage tractors and farm equipment, and even an ice-cooled refrigerator car that tells the story of moving Kern County's potato harvest to market.

If you're on the Central Coast, check out the 1870s Southern Pacific freight depot in Salinas, now home to a California Welcome Center. The Salinas Valley Tourism and Visitors Bureau has an exhibit titled "Postcards, Passengers and Produce, The Story of How Southern Pacific Company Created the Salad Bowl of the World" in the restored depot, next door to the 1942 passenger depot that still serves local transit and Amtrak trains.

Sacramento has been home since 1981 to the California State Railroad Museum, launched with a collection of locomotives and railcars gathered over the preceding several decades by the Pacific Coast Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society. Among the pieces: a 1924-vintage, ice-cooled refrigerator car. This car hosts "Farm to Fork: A Public History," which tells the story of the railroad's role in spreading California's agricultural products around the country.