Their place in the sun

Photo: Matt Salvo

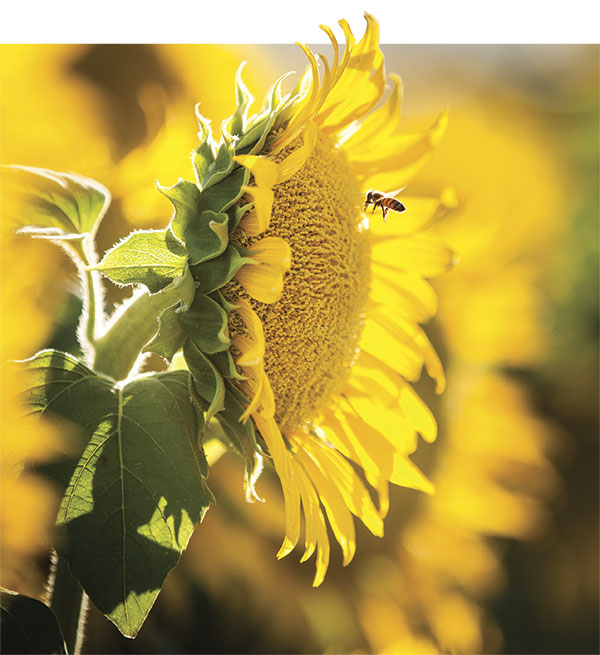

Take a drive through the Sacramento Valley countryside this time of year and chances are you'll encounter the brilliant, golden faces of sunflowers that would inspire Vincent Van Gogh to pull out his paintbrush.

So striking are the blooms that Yolo County farmer Jason Hatanaka has gotten used to the attention his fields often attract during the summer months, when travelers park their cars on the side of the road to admire the crop and take advantage of the photo op.

"When they're full heads and flowered out, people stop and take pictures of our sunflower fields because they're pretty," he said. "Some people take pictures of the actual flower and some will use the field as a backdrop for their family photos."

As stunning as his crop is, Hatanaka isn't growing the flowers for their mere beauty. Most of the state's sunflowers are grown for their seed—but not the kind you eat at baseball games. They are the planting seeds other farmers use to grow more sunflowers, primarily for making sunflower oil.

"The seeds are shipped all over the world," said Rachael Long, a University of California farm advisor.

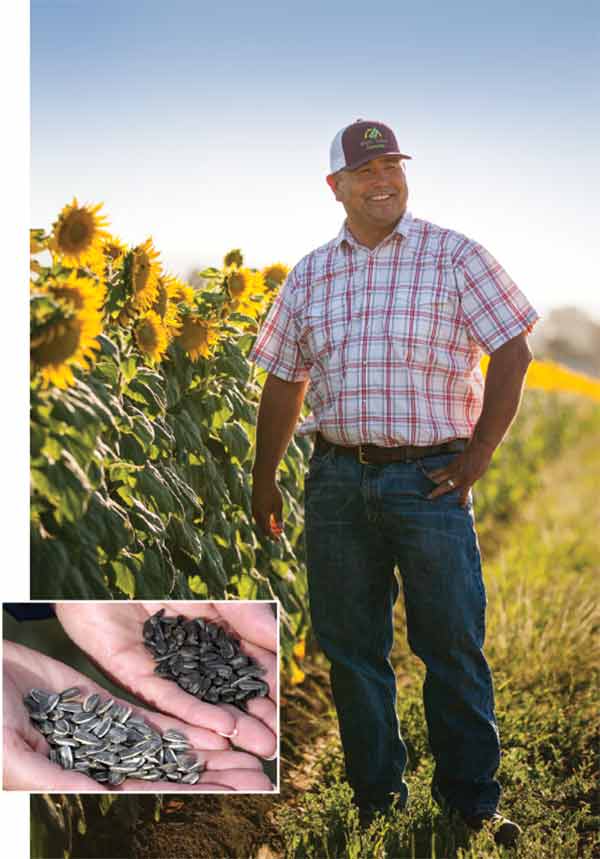

Carl Hjerpe, left, owner and manager of Reliance Seed Services, stands with Yolo County farmer Jason Hatanaka in a field of sunflowers. Seeds harvested from these flowers will be used by other farmers to grow more sunflowers. Photo: Matt Salvo

More than just a pretty face

The wild sunflower is indigenous to North America and was first cultivated by Native Americans, who found myriad uses for the plant, including making flour and oil with the seeds, drying the stalks for building and turning other parts of the plant into dye, body paint and ointments.

Later, sunflower oil became widely used in Russia, in large part because of a Russian Orthodox Church ban on the consumption of animal fats such as butter and lard during Lent. This catapulted the popularity of sunflower oil and led to the commercialization of the crop.

Today, Russia and Ukraine are the world's top sunflower producers, growing some 20 million acres. The European Union, Argentina, China, Turkey and India also grow a significant amount. In the U.S., the Dakotas is where you'll find nearly 80 percent of the nation's 1.5 million acres of sunflowers, even though Kansas is known as "the Sunflower State."

Regardless of where they're grown, many of those crops get their start in the Sacramento Valley, California's epicenter for sunflower seed production. Yolo County grows about 75 percent of the state's 43,000 acres, with Sutter, Colusa, Solano and Glenn counties accounting for much of the rest. There's good reason the region is coveted by major seed companies that breed, develop and produce sunflower seeds, Long said.

"Sunflower seed production requires warm, dry days and cool nights, because bees work really well under those conditions and you get good pollination," she said.

If temperatures get too hot, the flowers retract, preventing bees from accessing the pollen. In other areas such as the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, where wild sunflower populations are more abundant, it is difficult to grow hybrid planting seeds because of cross-pollination with wild sunflowers, Long added.

Hybrid seeds are produced by carefully controlling the pollination of two different varieties—that is, by crossing a male and a female to produce desired characteristics such as better disease resistance, higher yields, crop uniformity and, in the case of sunflowers, more oil content.

Jason Hatanaka plants both male and female sunflowers in his fields. Without males, the females wouldn't be able to produce seed. Photo: Matt Salvo

It's all in the timing

Carl Hjerpe, owner and manager of Reliance Seed Services in Capay, has been in the sunflower seed-producing business for 30 years. Seed companies turn to him to grow their seeds. He then works with farmers such as Hatanaka to make it happen. Planting usually starts in early April.

The biggest challenge seed producers face, he said, is trying to isolate the crop so there's no accidental cross-pollination with other pollen sources. That means separating different sunflower fields at least a mile and a quarter apart or staggering the plantings so they don't bloom at the same time.

"There's a lot to it because it's insect pollinated," Hjerpe said. "So my varieties have to be separate, not only from one another, but they have to be separate from all the other companies' varieties."

At the start of each year, seed companies stake their claim with pins on a map of where they intend to grow their seeds and make sure they don't encroach on someone's area, he said.

Isolation is one reason California is designated for seed production, Long said, and why there's not much sunflower production of any other kind, as that would "tie up a huge area and nobody would be able to grow the seed."

The fields are planted with both male and female sunflowers. The females don't produce pollen, and without the males, they can't produce seed. Timing is everything, as the males and females typically don't bloom simultaneously. The males, which have branched stems with multiple flower heads, can bloom for about three weeks, whereas the females produce only one flower and are receptive for about eight days. To ensure pollination, growers schedule their plantings so the males and females bloom in the field at the same time.

"We need the bees to touch every flower," Hatanaka said. "That's what makes our crop."

Sunflowers grown for oil have small, black seeds, while sunflowers grown for snacking have larger seeds with black and white stripes. Photo left: Shutterstock. Photo right: Matt Salvo

From golden to brown

Prior to bloom, work crews walk through the fields to remove "rogue" plants—sunflowers that are of a different variety, such as wild sunflowers or volunteers from the previous year. This is done so pollen from these off-types don't cross-pollinate with the crop.

"Basically, we have to clean up everything," Hjerpe said. "We have to drive the roads and pull out sunflowers that are on the roadside. If we find some in people's backyards, we stop and visit with them and explain to them what we're doing and see if we can remove their sunflowers from their backyards."

After pollination and when the seeds are set, the farmer removes the male plants from the field, as they won't be harvested. By this time, the crop is no longer irrigated. Meanwhile, the seed-bearing females are left in the field to mature, die and dry out. When the fields have turned brown, the seeds are ready to be harvested. Seeds harvested too young won't germinate, Hjerpe said.

Whether the seeds end up being planted by farmers in the Dakotas or overseas, most sunflower crops are harvested for their seeds. The majority are crushed for oil, which is valued for its light taste, frying performance and health benefits, and is often the oil of choice for potato-chip makers. Some seeds are sold for snacking, baking or topping salads. Sunflower seeds are also a popular bird feed. A small percentage is grown as cut flowers to be used in floral arrangements.

For farmer Hatanaka, sunflowers not only help pay the bills but also give him a different crop to grow after tomatoes.

"If they're pretty, that's great," he said.

What's in a name

Photo: Matt Salvo

Young sunflowers follow the movement of the sun throughout the day, a phenomenon known as heliotropism. Their heads face east at dawn and then gradually swing westward as the sun moves across the sky. The buds reorient at night, turning back east to anticipate the dawn and start the cycle again.

This behavior is driven by the plant's internal clock, which also regulates its growth, according to researchers at the University of California, Davis. As the flowers mature and their growth slows down, they stop tracking the sun and only face east.

Fun facts

- Wild sunflowers have multiple heads and are considered weeds.

- About 90 percent of sunflowers grown in the U.S. are harvested for the seeds' oil.

- Sunflowers grown for oil have small, black seeds, while sunflowers grown for snacking, or what's known as confectionary sunflowers, have larger seeds with black and white stripes.

More online: Gardening: Something new under the sun

More online: Gardening: Something new under the sun